Puzzle in Stone: The Cathedral at Glendalough

The ruined cathedral, the largest surviving church at Glendalough, consists of a nave and chancel with a sacristy attached to the south side of the chancel. The nave with its antae (projections of the side walls beyond the end walls) is clearly the oldest part of the building and was originally a single-cell rectangular church, possibly dating from the tenth or eleventh century. However, it has a number of peculiarities.

The most obvious of these is the use of large rectangular facing stones of mica schist in the lower courses of the walls. A second peculiarity is the fact that the antae are narrower than the walls of the building when normally antae are the same thickness as the walls. The main west doorway is unusual in having an arch over the lintel and in having its raised architrave broken by a flat-faced stone at each side just below the lintel.

There are also four mysterious D-shaped stones reused in the walls, though one was removed to St Kevin’s Church about 100 years ago.

The Hitherto Accepted Explanation

As with many of our most important National Monuments, little serious study has been carried out on the churches at Glendalough. The initial survey and description carried out by Robert Cochrane, Inspector of National Monuments, and published in the Report of the Commissioners for Public Works in Ireland for the years 1911–12 has in many ways not been surpassed. This fine survey was also published separately as the official guidebook to the site (see Archaeology Ireland Vol. 12, No. 4).

This guidebook was updated and revised a couple of times by H. G. Leask, also Inspector of National Monuments, and was in print until recently.

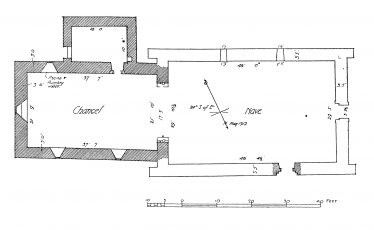

Cochrane recognised the great contrast between the cyclopean or large-stone masonry at the base of the walls and the rubble masonry above and postulated some interruption in the work. He showed the walls of the nave on his plan as being basically of one phase. Leask qualified Cochrane’s ‘interruption’ by adding ‘change of plan, or more probably, a complete rebuilding’, and altered Cochrane’s plan and sections to indicate that the rubble masonry in the upper parts of the walls belonged to a different phase from the cyclopean work below.

While Cochrane’s opinion on the building was not unreasonable, Leask’s embellishment of it was seriously flawed and lacked basic logic but, strangely, has remained unchallenged. To argue that the two types of masonry represent two phases, as Leask indicates in his plan and sections, would suggest that this building was originally brought up to full height in cyclopean masonry. Then for some reason the upper parts only of all the walls were demolished and then rebuilt in rubble masonry with none of the large stones being reused.

This defies logic because large portions of walls were not taken down and rebuilt without good reason such as foundation failure, and if the foundations failed the entire wall would have to be rebuilt, not just the upper parts. Also, if the walls were rebuilt in rubble rather than with the original stones, a large amount of cyclopean masonry would have been available for reuse after phase 2 and would surely have been used in some other building on the site, but there is no evidence for this (apart from one of the antae stones on the ground to the east of St Kevin’s Church).

Françoise Henry, in her three-volume work on early Irish art, reiterated Leask’s arguments enthusiastically, thereby compounding their illogicality.

A More Likely Solution

The inescapable conclusion is that the cyclopean masonry and the rubble masonry belong to one building phase. The reason the large stones are there is that they were reused from an earlier smaller church on the same site which was fully demolished.

In building the larger church the old facing stones were reused; this recycled material ran out at a height of three or four courses, and building continued upwards in ordinary rubble masonry. If further proof were required, there are tell-tale signs in the cyclopean masonry that these stones are not in their original positions. Joggled joints are sometimes found in this type of masonry, whereby a corner is cut out of one stone to accommodate the projecting corner of another.

In their present location some of these large stones have corners neatly cut out of them for no apparent purpose, to be filled only with a piece of rubble masonry. In the exterior face of the north wall near its base there is a large stone with what appears to be a rounded window-head cut into it, which makes no sense in its present location. Clearly all of these large stones are in a secondary location.

An examination of the antae shows that many of the stones used in them came from the older church. These are large in size, are also of mica schist and, strangely, have chamfered corners. As already pointed out, the antae (0.82m wide) are narrower than the walls of the church (1.04m wide) but, again strangely, they were widened at the top to the full thickness of the wall, indicating that the builders were conscious of this disparity and wished to have the upper bearing surfaces of the antae as wide as the walls of the church to hold the end rafters of the roof.

Some of the stones in the antae are the full width of the antae, with both corners chamfered, and clearly this was the width of the antae of the older church; consequently this measurement (0.82m) was also the width of the walls of the older church.

The west doorway was also reused from the older church but it was heightened—hence the stone at each side with no architrave moulding— and widened slightly. But, most interestingly of all, if we place this doorway within the thinner wall of the earlier church, its narrow inner jambs would have projected into the church and the two sets of rectangular holes in them would have served much better for securing the door from the inside, as wooden beams could have been inserted right through the slots from either side.

The arch above the lintel with the semicircular space between, now filled with rubble masonry, was probably also a feature of the doorway in its original position, as will be seen below.

The D-shaped Stones

Confusion as to the purpose of the D-shaped stones can be traced back to Cochrane, who claimed that they were parts of engaged columns from the chancel arch of an earlier church. This theory does not stack up because the stones do not stack up: they are of varying widths and could never have been part of a column or pair of columns. Anyone with a hand-tape could have disproved this theory in five minutes, yet until recently it was still trotted out as possible evidence that the first stone cathedral at Glendalough had a chancel and chancel arch, thereby utterly confusing the relatively simple typology of early masonry churches.

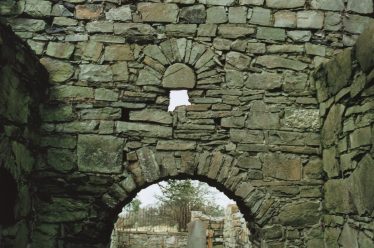

The explanation for these D-shaped stones can be found in an interesting ruined church at Confey, Co. Kildare. The original building there was a simple rectangular church without antae, which was later extended westwards and had a narrower chancel added at its east end. A rounded chancel arch was inserted into the east wall of the earlier church but the upper part of the original east window survives above the chancel arch, and its external head consists of a D-shaped stone with an arch around it. Two windows survive in the south wall of the nave.

The westernmost is clearly an insertion. The easternmost belongs to the first phase and again has a D-shaped stone and arch externally, though the D shape is not as perfect as in the east window. Most of the surviving pre-Romanesque churches in Ireland had only two windows, one in the centre of the east wall and one towards the east end of the south wall. Therefore if the original stone church at Glendalough had two windows like those at Confey that could explain two of the D-shaped stones. The other two could have been the internal and external tympana for the original west doorway.

The two windows in the south wall of the nave are also puzzling, especially the easternmost, which consists externally of finely carved stones forming parallel jambs and a rounded head cut out of a single stone. Undoubtedly reused, these stones look as if they originally formed a doorway but for an even thinner wall than that of the older church.

Maybe more than one church was demolished to make way for the nave of Glendalough cathedral. There are also puzzling stones with very finely carved rebated edges reused in the inner face of the north wall. Finally two stones in the south-west anta have unexplained projections.

Discussion and Dating

Françoise Henry put forward a very weak argument for dating the nave of the cathedral to the eighth century: ‘From the middle of the eighth century Glendalough figures prominently in the Annals, so that there does not seem to be much reason to hesitate in dating it to that time’.

I have argued that one of the earliest stone churches to survive in Ireland is Clonmacnoise cathedral, built in AD 909 (Archaeology Ireland Vol. 9, No. 4), and, while the present nave of Glendalough cathedral is superficially similar, features such as the antae were derived from the earlier church, though the fact that they were widened at the top shows that they still served their original purpose. Unlike at Clonmacnoise, the annals are of no assistance in dating the cathedral in Glendalough or its stone predecessor. It is probably best to discuss the earlier church first and then the present nave.

The Earlier Church

Despite the fact that no portion of this church is still standing, we know a surprising amount about it: the thickness and facing stones of its walls; the thickness, rough height and appearance of its antae; the exact appearance and dimensions of its unusual doorway; and the likely appearance of its two windows. The fact that there are few, if any, large stones with gable angles suggests that the triangular portions of the gables may have been timber-framed structures.

It must have been an unusual church and nothing survives elsewhere that is closely comparable in all of its features. Antae are normal in tenth-century churches and a parallel for the chamfered corners on the antae can be seen at Longfordpass church (originally Daire Mór), Co. Tipperary. The doorway is unique among pre-Romanesque churches in Ireland, especially in its accommodation of the door itself within the opening, a feature of doorways of the later medieval period.

The tympana at each side over the doorway are paralleled at St Kevin’s Church less than 50m away (the stones of which have also been reused) and in pre-invasion churches in England. Tympana over the windows are paralleled at Confey, an otherwise typical stone church of about the eleventh century. It is possible that Confey, a church in the diocese of Glendalough, got the inspiration for this feature from the church at Glendalough, though there may have been intermediaries no longer extant.

This church is likely to have been the first stone church at Glendalough. Its unusual features, some virtually unique, might indicate an early date in the series. It does not appear to have been copied widely, apart from the features mentioned above, and later stone churches at Glendalough owe more to the general Irish tradition of church-building in stone.

The pre-789 stone church at Armagh, which we know of only from the annals, and the partly surviving 909 church at Clonmacnoise (the cathedral) may have been more influential. The original stone church at Glendalough may have been built within this span of time, with possible influences from Britain on its doorway and windows. Taking all factors into account, a date in the late ninth or early tenth century is a possibility for this early stone church.

The Influence of Wooden Churches

Because the same master wrights (saoir in Irish) made the transition from building churches in timber to building them in stone, it is only to be expected that the stone buildings would be influenced by the timber building tradition.

Antae, a feature unique to Irish churches, may be derived from the earlier oak churches (dairtige), which may have had projecting uprights at the corners to carry the ends of the roof over the gables. The chamfer on the corners of the antae, which worried certain commentators because it is usually a later medieval feature, is a common and practical feature of most woodworking traditions.

The simple raised architrave around the doorway is likely to be a copy in stone of the heavy frame of the doorway of a wooden church. Even the use of large, thin facing slabs in the walls could be seen as reminiscent of timber boards.

The Present Nave

This is also difficult to date, especially because some of its features are from the earlier church. The presence of two original windows in the south wall is a feature unparalleled before the twelfth century (compare Reefert church further up the valley at Glendalough), but then its rubble masonry has putlog holes like at Clonmacnoise and its antae are functional and not just anachronistic features.

On balance a tenth-century date cannot be ruled out, with its pair of windows in the south wall being just an exception to the rule. The later history of the building, involving the addition c.1200 of a chancel and sacristy and a doorway in the north wall, is also of great interest.

One of the most striking features of the cathedral at Glendalough is the reuse of large cut stones in the lower courses of the walls of its nave. These, along with its west doorway and antae, are literally a jigsaw puzzle with the potential to tell us not only what an earlier church on this site looked like but also something of what early medieval wooden churches in Ireland were like.

Illustrations

1. The nave of the cathedral from the west (J. Scarry).

2. Cochrane’s plan of the cathedral.

3. A joggled joint, as it would have been originally, in the inner face of the west wall, north of the doorway (C. Manning).

4. A notched stone serving no purpose in its present position (C. Manning).

5. The north-west anta with a corner chamfer visible on some of its stones (J. Scarry).

6. An exterior view of the west doorway (J. Scarry).

7. The west doorway from within, showing two slots for beams to secure the door from the inside (J. Scarry).

8. Two D-shaped stones built into the north-west corner of the nave (J. Scarry).

9. An external view of the original east window of Confey church with D-shaped stone tympanum in place. The lower part of this window was removed when a chancel arch was inserted in the wall (C. Manning).

10. The south-west anta of the cathedral (J. Scarry).

11. An interior view of the south wall of the nave, showing the two windows (J. Scarry).

This Article is provided courtesy of Con Manning & Wordwell Publishing and first appeared inArchaeology Ireland, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Summer, 2002), pp. 18-21

No Comments

Add a comment about this page