The Beauties of Ireland (excerpt - published 1825)

Such are the mountainous wilds

Such are the mountainous wilds amidst which, in deep solitude and awful quiet, is situated Glendalogh, celebrated in early ages of christianity for the comparative splendour of its religious piles, and for a city of considerable population ; now a melancholy waste, romantic in character, and rich in antiquities, but visited by few, except the curious traveller and fanciful pilgrim.

Previous to a description of this singular glen, and a notice of its architectural vestiges, it must be desirable that we should present an outline of historical intelligence respecting its rise in celebrity, and the circumstances which caused it to be abandoned as a place

of residence.

St. Coemgene, or Keivin, by which latter appellation he is usually distinguished, is said to have descended from a noble family, and was born in the year 498. At the age of seven years

he was placed under the care and tuition of Petrocus, a Briton, who had passed many years in Ireland for the exercise of learning.

After pursuing his more advanced studies, for a considerable time, in the “cell of three holy anachorites,” St. Keivin embraced the monastic profession. On taking upon him the cowl, he retired, says Archdall, ” to these wilds, where he wrote many learned works.”

It is generally admitted that he founded an abbey at Glendalogh, and presided here as abbot and bishop for many years. He died on the 3rd of June, 618, ” having nearly completed the uncommon and venerable age of 120 years.”

The eminent virtues and exemplary sanctity of this holy man

The eminent virtues and exemplary sanctity of this holy man, and the miracles said to have been wrought by him, drew, as we are told by the author of Monasticon Hibernicum, “multitudes from towns and cities, from ease and affluence, from the care and avocations of civil life, and from the comforts and joys of society, to be spectators of his pious acts and sharers in his merits, and, with him, to encounter every severity of climate and condition. This influence extended even to Britain, and induced St.Mochuorog to convey himself hither, who fixed his residence in a cell on the east side of Glendalogh, where a city soon sprang up, and a seminary was founded, from whence were sent forth many saints and exemplary men, whose sanctity and learning diffused around the western world that universal light of letters and religion, which, in the earlier ages, shone so resplendent throughout this remote and at that time tranquil isle, and were almost exclusively confined to it.”

It is supposed by Mr. Harris that St. Keivin first founded the church of Glendalogh as an abbey only; but it is sufficiently evident that this place speedily grew into the see of a bishop. The diocess of Glendalogh was of great extent, and comprised nearly all the country in the vicinity of Dublin.

It is observed by the same writer, in his edition of Ware’s Antiquities, (vol. i. p. 371) that “in the confirmation of Pope Alexander III., of the possessions of this see to Malchus, Bishop of Glendaloch, A. D. 1179, we find no less than fifty denominations, or particulars, recited; and that Dublin itself stood in the diocess of Glendaloch, is mentioned in the preamble of the bull of Pope Honorius III. A. D. 1216; whereby that pope confirms the union that Paparo

had made.”

The See of Glendalogh

The see of Glendalogh subsisted until the reign of King John, at which time the diocess was united with that of Dublin. But it would appear that this was considered, by many, as an objectionable stretch of power, and the measure was naturally opposed by the sept of O’Toole, within whose territory stood the ancient see.

It has been conjectured that the see was kept constantly filled by that sept for many succeeding ages, although the temporalities were principally estranged. Many instances of this “usurpation” are recorded. Friar Dennis White, the last of these nominal prelates, surrendered his possession in the year 1497, and the archbishops of Dublin have ever since presided over the united sees, without interruption.

Some scanty materials collected by Mr. Archdall towards the history of the Abbey of Glendalogh, involve several particulars relating to the annals of the city. But his authorities deal in no other than the prominent events of fire, massacre, and rapine; and, unhappily, this city of the mountains afforded a prolific theme for the labours of such annalists. We decline a chronological detail of the enormities here practised, but it may be proper to notice some of the principal of these woful occurrences.

In the year 770, Glendalogh was destroyed by fire

In the year 770, Glendalogh was destroyed by fire; and in 830, the abbey was plundered by the Danes. The ravages committed by that people were so frequently repeated, that we may condense the intelligence respecting their aggressions, by observing that they appear to have considered this religious retreat as a depository of rich offerings, to be emptied by sacrilegious avarice as soon as replenished by votive piety.

In the year 1020, “Glendalogh was reduced by fire to a heap of ruins;” and we are told that thrice, in an advanced part of the same century, the city was consumed by accidental conflagration.

Trifling particulars may not be altogether devoid of interest, when they relate to a place of which scarcely any domestic traces, or civic records, are now remaining; and we, therefore, mention that, in 1177, “an astonishing flood ran through this city, by which the bridge and mills were swept away, and fishes remained in the midst of the town.”

In 1309, Piers de Gaveston, the well-known favourite of Edward II defeated the sept of O’Byrne in this neighbourhood. He “rebuilt the castles of Mac Adam and Keivin ; cut down and scowered the pass between Castle-Keivin and Glendalogh, in despite of the Irish; and then made his offering at the shrine of St. Keivin.” In the summer of 1398, the English forces, as we learn from the “Annals of the Four Masters,” burnt and destroyed the city.

Never recovered from the injuries

It would appear that Glendalogh, long declining, never recovered from the injuries then inflicted, but has, ever since, remained a dejected solitude, the theme of no other pages than those of the antiquary and poet . We may add to the above broad features in the annals of this deserted glen, that, on the 25th of August, 1580, an English force commanded by Lord Grey de Wilton, was here defeated, with considerable loss, by the Irish under Pheagh Mac Hugh O’Byrne, and Eustace, Viscount Baltinglass. The queen’s troops, writes Leland, “had to enter a steep, marshy, valley, perplexed with rocks, and winding irregularly through hills thickly wooded. As they advanced, they found themselves more and more encumbered; and either sunk into the yielding soil, so as to be utterly incapable of action, or were obliged to clamber over rocks which disordered their march.

In the midst of confusion and distress, a sudden volley from the woods was poured in upon them, without any appearance of an enemy; and repeated with terrible execution. Soldiers and officers fell, without any fair opportunity of signalizing their valour. Audley, Moore, Cosby, and Sir Peter Carew, all distinguished officers, were slain in this rash adventure.”

Glendalogh is situated in the barony of Ballinacor

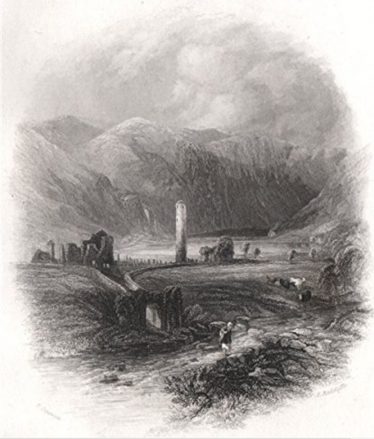

Glendalogh is situated in the barony of Ballinacor, at the distance of about twenty-four miles from Dublin, towards the south. The name is derived, like most other early denominations of places, from obvious and characteristic natural features, and implies the glen, or valley, of the two lakes. The glen extends from east to west, and is open in the former direction, but enclosed in every other part by steep and lofty mountains. A singular and striking view of the scene which the traveller is approaching, may be obtained from the neighbourhood of the barracks, not far from the opening of the vale towards the east.

These perishing relics

The sequestered recesses of this solemn tract are here partially revealed, rich in a group of ruins, above which rises a stately round tower. Behind these perishing relics (the sole remains of the city!) rises an abrupt and very lofty mountain, of fantastic shape.

Near its commencement the vale is of an expanded and a comparatively cheerful character, with broad but neglected tracts of meadow, or pasture, watered by the flow of the Avonmore. But the mountains speedily relinquish their shelving positions, draw nearer in a fearful abruptness of ascent, and spread a thick mantle of gloom over the consecrated but forsaken district.

The first architectural object which arrests attention is a building whose antient appellation is forgotten, and which is now known only by a name familiarly borrowed from the vestment which screens its decay ;—that of the Ivy Church. This ruin is situated to the south of the traveller’s progress, and near the customary path.

On the opposite side of the river

On the opposite side of the river, towards the south-east, are the remains of a building called by Mr. Archdall and Dr. Ledwich, the Priory of St. Saviour, and a chapel, which had been

buried in obscurity for many ages, and was discovered only a few years back.

At the distance of about a furlong to the west of the Ivy Church, we reach the former market-place of the city; to the south of which are the cathedral; a round tower; St. Keivin’s Kitchen; and other remains of ecclesiastical buildings.

Nearly in the middle of the glen are the ruins of the abbey. The two lakes which afford an appellation to this glen, are situated to the west of the cathedral and the site of the antient

city. These are divided by a watery meadow; and a cataract enriches the interstice of two mountains, towards the south.

Here, on the strip of land between the waters, is the stony path of pilgrimage ; and the ruins of several crosses, and of a circle of stones, denote the places of former ceremonials. Here, also, we approach the Rhefeart church, or burial place of kings ; and the excavation of a lofty rock, termed St. Keivin’s bed.

Glendalogh stands revealed in all the awful tranquillity

We are now arrived at the spot in which Glendalogh stands revealed in all the awful tranquillity which induced the selection of this place by St. Keivin and his followers, as a recess marked by the hand of nature for deep religious meditation.

The lakes are thrown into solemn shade by precipitous mountains of a sable tincture, which shut the profound waters from familiar visitation, and form a world peculiarly their own, more fearful, black, and like the quiet of the grave, than man can sustain, for a continuance, when under the influence of his wonted habits.

It is the region of the Eremite

It is the region of the Eremite; it is the inspiring territory of the tragic poet, when embodying monstrous images that would appear to have issued from the womb of night, thrown into a frightful half-existence by distempered dreams . The gloom of this scenery overcomes the buoyancy of man’s spirit, and the tones of worldly converse seem profanation.

Oppressed to extreme dejection, we look for relief to the avenue by which we entered ; and there, in a tract approaching, although faintly, to the complexion of ordinary life, behold the

unrecorded ruins of a religious city—the Palmyra of the desart!

That this picture is not overcharged, will be readily admitted by those who visit Glendalogh; and the antiquities presented by the vale are highly worthy of investigation. We have already

suggested that the best guides, in an examination of these ruins, are confused and defective. Even the identity of the Seven Churches is quite open to discussion; but we believe that these structures may, with some hope of correctness, be enumerated as follows:—1. The Cathedral. 2. The Abbey. 3. St. Keivin’s Kitchen. 4. Our Lady’s Church. 5. The Rhefeart Church. 6. Teampull-na-Skellig. 7- The Ivy Church.

The principal ruins of Glendalogh

In our notice of the principal ruins of Glendalogh, we commence at the east, and pursue a western progress throughout the valley.

The Ivy Church

The Ivy Church is small and of rude construction, the walls being formed of unhewn stones, dissimilar in size. This building is roofless, and in the last stage of decay. The entrance to the body of the church is by a narrow and square-headed doorway ; and in that part of the structure there now remains only one window, about two feet high, and ten inches in width; round-headed, and the sides expanding towards the interior. At the east end is a semi-circular arch, of large dimensions, very coarsely executed, leading to a small attached building, in which are two windows, one round-headed, and the other forming a point, by means of two slabs of stone inclining towards each other, and meeting at the top. At the west end was lately a circular tower, of moderate height and diameter, evidently designed for a belfry ; but this part of the building was of very different masonry to the tall pillar-towers of Ireland, and fell to the ground in the winter of 1818.

The Abbey, which was dedicated to St. Peter and St. Paul

The Abbey, which was dedicated to St. Peter and St. Paul, is now in so ruinous a condition as to have lost nearly all traces of architectural character. The earth rises in wavy hillocks over

its fallen enrichments, and matted trees and brambles overgrow the decayed walls. The description of these remains, in their existing state, may be nearly comprised in the above sentence; but so vivid a degree of curiosity is naturally excited by this antient pile, that we extract, and present in the margin, some observations made on this spot by the late Mr. Archdall, about forty years back.

Amongst the most curious architectural vestiges of Glendalogh must be noticed a small Chapel, or Oratory, which had lain buried for ages beneath the ruins of a contiguous church, and was restored to the light of day by the antiquarian zeal of the ate Samuel Hayes, of Avondale, Esq.

The remains of this building exhibit few traces of architectural style, but afford some

specimens of antient sculpture, which, although rude, are of great interest. The chapel is about fourteen feet in length, by ten feet in width, and has been supposed to contain the tomb of St. Keivin. The entrance is by a doorway towards the west, the decayed arch of which, and the capitals and bases of the pillars, are adorned with various carvings, in faint relief. In describing the subjects of these carvings we take advantage of some remarks

afforded by Dr. Ledwich, whose observations are usually of unequivocal value, where description alone is the object in request.

A ravenous quadruped, probably a wolf, gnawing a human head

The following are the principal subjects represented. A ravenous quadruped, probably a wolf, gnawing a human head. The head is large, and the hair, beard, and whiskers unite in be

stowing on it a savage appearance.—The head of a young man and a wolf; the longhair of the man entwined with the tail of the beast. The author by whom we profit in our notice of this chapel, observes that ” the hair thus thrown back from the forehead was the genuine Irish Culan, Cooleen, or Glibb. Wolves, until the year 1710, were not extirpated, and the mountains of Glendaloch must have abounded with them.

There was a singular propriety in joining the tail of this animal with the young man’s glibb,

to indicate the fondness of the one for the pursuit of the other.”—A triangle, enclosing a wolf, holding the end of its tail in its mouth.—Two ravens picking a skull, the whole enclosed in a triangle. Dr. Ledwich observes that this bird was peculiarly sacred to Odin, who has been called the King of ravens.—A central human head, with a wolf on each side, feeding on it.

To represent Runic Knots

Various intersecting segments of circles, supposed to represent Runic Knots. Dr. Ledwich quotes Keysler to show that ” there were seven kinds of Runes, adapted to promote every human action and wish according to the ceremonies used in writing them; the materials on which they were written; the place where they were exposed; and the manner in which they were drawn; whether in the form of a circle, a serpent, a triangle,” or otherwise.

From the character of these devices, the author of the ” Antiquities of Ireland” ascribes, without hesitation, the origin of the structure to the Danes. Here (writes Dr. Ledwich) ” are no

traces of Saxon feuillage, no christian symbols, no illusions to sacred or legendary story : the sculptures are expressive of a savage and uncultivated state of society;” and, therefore, as is clearly implied by his remarks, the work is not Irish but Danish. It maybe observed that in the sculpture at Mount-Cashell, which few will suppose to have been executed under Danish patronage, there is no device that can be deemed a ” christian symbol ;” and it is well known that the grotesque carvings used for church-ornaments by the Anglo-Normans, were often equally destitute of pious reference.

The useful and dangerous chase of the wolf

We might expatiate on the improbability of an artist under Danish protection introducing a head confessedly Irish, with the complimentary allusion of attachment to the useful and dangerous chase of the wolf. But our limits prevent an ample discussion of such topics ; and we must rest contented with briefly remarking, that, since the Danes are known to have so frequently ravaged with sword and firebrand the consecrated recesses of this valley, it must be deemed extremely unlikely that they were, at the same time, the founders and superintendants of a costly religious edifice in the vicinity of its abbey.

Dr. Ledwich would appear to insinuate, (in page 181 of his ” Antiquities of Ireland”)

that the Danes ” pillaged their own countrymen” when they burst with a sacrilegious hand into the feeble sanctuary of Glendalogh; but if he believe that they had really effected a stationary residence in this mountainous part of the territory of the OTooles, he will certainly not make converts to such an opinion.

In ascribing this building to invaders from the north, our author appears to be chiefly influenced by his favourite assertion that masonry “was not practised in this land before the establishment of the Danish power in the tenth century;” a position which, we think, will remain untenable whilst the stupendous round tower of this vale rears its massy and finely-wrought form, in a district continually ” pillaged” by that savage people.

The market-place of the fallen city

On pursuing the customary path from the Ivy Church towards the west, we speedily arrive at the former centre of busy congress, the market-place of the fallen city! This is a small and square plot of ground, the surface now uneven and overgrown with grass. In the middle stood a cross, of which the base still remains. No traces of antient domestic buildings were discovered in our researches; but the city is supposed to have extended from the Rhefeart church on the west to the Ivy Church on the east; and to have stood on both sides of the river. The remains of a paved street, about ten feet in width, are still visible for a considerable extent, leading from the market-place into the county of Kildare. A few small cabins are inhabited by peasant families, who readily act as guides to the inquisitive visiter.

The Cathedral

To the south of the market-place we pass over the river Glendasan (a shallow brook in the summer, but a torrent of much fury when swoln with the rains of winter) by means of stepping stones; and then approach the cathedral. That church is surrounded by a spacious cemetery, entered by a double gateway of semi-circular arches, composed of large stones rudely hewn.

Within the limits of the cemetery is a round or pillar tower, 110 feet in height, and fifty-two feet in girth near the bottom. The roofing is gone, but the tower is, otherwise, in excellent preservation. The entrance is by a round-headed doorway, about 10 feet from the ground. In different stages of the ascent there are, as usual, several small apertures, which are of a square form.

In the south part of the same cemetery is a plain cross, formed of one entire stone, eleven feet in height.

The Cathedral is of small dimensions, the nave being forty eight feet in length by thirty feet in width. The whole is in a ruinous state, and of rude architecture. The original windows were small, and in the circular mode of design; but, with one exception, were destitute of ornament. The chancel is divided from the body of the church by a semi-circular arch; and, at the eastern end, are the remains of a window, now greatly mutilated, but formerly exhibiting much curious decoration. The head is semi-circular, and the sides are cut away with consider able skill, thus causing the aperture to be large within, whilst the actual perforation of the wall is scarcely of greater width than the arrow-loop of an antient castle.

The sweep of the arch is ornamented with chevron work; and a broad impost-moulding

formerly contained many pieces of legendary sculpture.

The priest’s-house…probably the Sacristy

At a small distance from the cathedral is a building, familiarly termed the priest’s-house , which was, probably, the sacristy. This is a structure of small dimensions, composed of unhewn stone, and now in a state of ruin.

The inappropriate appellation of St. Keivin’s Kitchen

The building commonly known by the inappropriate appellation of St. Keivin’s Kitchen, is nearly parallel with the cathedral. The walls of this chapel, or oratory, are constructed of rough stone, and are three feet six inches in thickness. The gloomy effect of twilight was evidently studied in the disposal of the interior, as there was originally only one window in the western division of the building. This was placed about eight feet from the south-east angle; and, as we learn from Mr. Archdall, was ornamented with an architrave of free-stone, “elegantly wrought, which was conveyed away by the neighbouring inhabitants, and brayed to powder for domestic use.” The eastern compartment is separated from the body of the chapel by a semi-circular arch, and is lighted by two narrow and round-headed apertures.

Towards the north is a small apartment, or chapel. It may be observed, that the part which we describe as the body of St. Keivin’s chapel, is of a greater height than the fabrics towards the east and north, and probably constituted the whole of the original building. The roof is composed of thin stones, laid horizontally, and rising in the form of a wedge to a sharp angle, the extreme height being about thirty feet. The ceiling is coved; and between the coving and the roof is a rude apartment, lighted by a small window. From the west end of the roof ascends a circular turret, designed for a belfry.

Our Lady’s Church

Our Lady’s Church is nearly opposite to the cathedral, and is now in a ruinous condition, and overgrown with ivy. The masonry, although far from excellent, appears to have been superior

to that observable in several of the other buildings.

The Rhefeart, or Sepulchre of Kings

The Rhefeart, or Sepulchre of Kings, is situated between the two lakes, and acquires its appellation from the circumstance of having afforded a place of burial to the princes of the race of O’Toole. This church is now a confused mass of ruin. The interior is filled with the fallen materials of the structure, amidst which have shot up trees, of various growth, some flourishing in early vigour, whilst others are themselves decayed through age.

The cemetery is overgrown

The cemetery is overgrown with brambles, and disfigured with fragments of the ruin. Here are to be discovered the mutilated remains of several crosses, which do not appear to have been richly worked, and are now covered with mosses. On a tomb in this church is an inscription, defaced through age, which is said to have presented the following words, in the Irish character :

Jesus Christ

Mile deach Fcuch Corp Re Mac M’Thuil.

Behold the resting-place of the body of King M’Thuil (or Mac Toole)

who died in Jesus Christ, 1010.

Between the cathedral and the tract to which we have now directed the reader’s attention, is a paved footway, over a marshy piece of ground in the strip of land that divides the two lakes.

This path, now overgrown with grass, was in the line of antient pilgrimage, and several crosses were erected in different parts of the pilgrim’s progress. These are now much injured by time and wanton hands, but appear, from their remains, to have been originally destitute of elaborate ornament. Near the first cross on leaving the Rhefeart church, is a circle of stones, piled up to the height of about three fee ; at, and round which, we are told,

the pilgrims performed penance.

Teampull-Na-Skellig… the Priory of the Rock

Situated in the recess of a mountain that rises to the south of the upper lake, was Teampull-Na-Skellig , often called the Priory of the Rock, or the Temple of the Desart ; names expressive of the Irish appellation. This was a small and rude fabric, extremely

difficult of approach.

In a rocky projection of the mountain, near the frightful site of this temple, is the celebrated Bed of St. Keivin. The place thus denominated is a cave, hewn in the perpendicular rock, at a

considerable height above the profound waters of the lake. A situation more appalling cannot be readily imagined. The path which leads to it is fearfully narrow, and one false step must inevitably plunge the adventurer into the lake beneath, which wears a black and threatening aspect, the reflection of the gloomy mountains by which it is surrounded.

There are many ruins of inferior ecclesiastical buildings

The above are the most prominent objects which require attention; but, besides the subjects which we have described, there are many ruins of inferior ecclesiastical buildings, left without a name amidst the spoils of time. These are of sufficient interest to merit examination by the visiter whose taste and leisure may favour extended researches ; but we are not aware that they afford any curious vestiges of architecture or sculpture. We shall make no apology for omitting to specify the various tales of wonder fondly cherished by the illiterate, respecting this sequestered glen.

The festival of St. Keivin

The festival of St. Keivin is annually celebrated on the 3rd of June, at which time,

” The mountain-nymphs and swains are seen,

Combining in the dance of mirth.

There many an awful tale is told,

Traditions of the times of old ;

Which the fond ears of wondering youth,

Devour as words of sacred truth.”

The OTooles remained a powerful sept

Glendalogh was the chief town of the territory denominated Imayle, or Hy-Mayle, the principality of O’Toole, on the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in this country. The OTooles remained a powerful sept for several centuries subsequent to that event, their possessions, at the date of the Norman invasion, extending to Castle-Dermott, in the modern county of Kildare, where the toparch generally resided, until dispossessed by de Riddesford, Baron of Bray.

The harassing wars in which the O’Tooles and O’Byrnes engaged against the English settlers, are narrated under nearly every reign in the history of Ireland, previous to the termination of the 16th century ; and, after a long interval of comparative tranquillity, the former sept appeared in arms so lately as the year 1641 ; a circumstance noticed in our account of the town of Wicklow.

St. Laurence O’Toole

One of the most illustrious persons of this name and lineage, was St. Laurence O’Toole, Archbishop of Dublin from the year 1162 to 1180, whose unquestionable worth has been recorded in several previous sections of our work. This excellent prelate was the son of Moriertach, Prince of Imayle, and received his education in the seminary of Glendalogh, in the monastery of which place he took upon him the habit of religion.

Since the troubles of the 17th century, in which every party bore a share, the family of O’Toole have maintained a more amiable, though a less important station in society, than in preceding ages. The present known representatives of this once-formidable sept are, O’Toole, Esq. of Edermyne, and Colonel John O’Toole, of Newtown, both in the county of Wexford. The latter very respectable gentleman was formerly an officer in the French service. He married the Lady Catharine Annesley, sister to the late Earl of Mountnorris, by which lady he has issue.

This article is an excerpt form the book ‘The Beauties of Ireland: Being Original Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Biographical of each County’. Published in 1825 by Sherwood, Jones & Co., London.

Kindly digitized by Google Books. Full text available here.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page