A Monastery Among the Glens

The placid waters and steep cliffs of the famous Upper Lake at Glendalough were said to have hidden a terrible secret. A great monster terrorised the people of the valley; it was defeated by St Kevin and confined to the Upper Lake. The various ‘lives’ of St Kevin tell how he moved his monastery from the Lower to the Upper Lake (or vice versa, depending on the version), from remote aesthetic hermitage to bustling civitas, before dying at the venerable age of 120 in AD 621.

These stories, written in the eleventh century, carry threads of truth wrapped around the Uí Mail and Uí Muireadaig dynasties who successively prized control of the site, but hard evidence for the early foundation of Glendalough is scant. The later stories also contain little detail about the material appearance of Glendalough at its peak of power before the thirteenth century.

Complex architectural history

The complex architectural history of the seven stone churches, round tower, gateway and stone sculptural monuments encodes complex messages about belief, monasticism and patronage from the tenth to the thirteenth century. This architectural legacy does not shed light on the enclosures, houses and pathways of the wider complex required to make these monumental buildings work.

Likewise, annalistic references tell us much about the political and ecclesiastical history of the civitas of Kevin. Apart, however, from sparse references to topographical features, churches, houses, a mill and roadways, there is little information on the physical make-up of this large settlement.

Understanding the character of the valley

The nineteenth- and early twentieth-century campaigns of reconstruction and conservation in the valley have made our interpretation of some of what does remain more difficult. Glendalough is a candidate World Heritage Site, but the gaps in our knowledge of the evolution of the landscape are significant. Besides the intrinsic interest in better understanding the character and distribution of archaeological material in the valley, the landscape at Glendalough is under immense pressure from increasing visitor numbers, and key debates exist around the management of so many visitors and appropriate resolution to questions about car- parking. These difficult decisions require good information about the archaeological heritage of the valley.

Targeted archaeological fieldwork

Targeted archaeological fieldwork is crucial to furthering our knowledge of the evolution of Glendalough and therefore securing the future of the archaeological resource in the valley. Given the iconic character of the Glendalough landscape, it is surprising that archaeological excavation and survey in the valley have only taken place sporadically since the 1950s. Since 2009 a systematic programme of excavation and survey by the UCD School of Archaeology has been investigating the evolution of the complex.

The project integrates research-led investigations, teaching and a substantial

commitment to community archaeology. This involves close co-operation with the National

Parks and Wildlife Service, the National Monuments Service, the OPW and Wicklow County Council.

Glendalough Heritage Forum

In 2015 we formed the Glendalough Heritage Forum, a non-statutory body including state agencies, researchers and the local community. The forum has been invaluable in developing a collaborative community archaeology project, including opportunities for local volunteers to participate on our excavations.

This article highlights some aspects of our ongoing research into the evolution of the monastic landscape. We start at the west of the valley, and move eastwards towards the

main monastic complex.

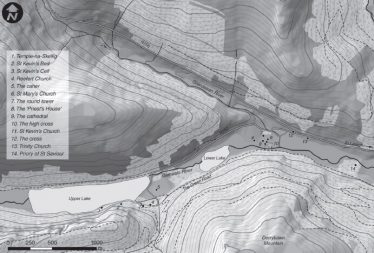

Temple-na-Skellig

UCD excavations in the valley began in the 1950s with Françoise Henry’s extensive investigations at Temple na Skellig (Fig. 1). This is the most westerly of Glendalough’s seven churches, now a remote location populated only by wild goats and the scourge of rhododendrons (see Fig. 2). Henry and a team of local men were rowed across the lake each day to the steep slopes on the southern edge of the Upper Lake.

The small Romanesque church lies close to the modified cave known as St Kevin’s Bed and forms an important part of the saint’s pilgrimage. Henry excavated a sequence of four subrectangular house sites, built with a mixture of schist stone and timber, set on terraced drystone revetted platforms adjacent to the church. They were linked by paths and steps of schist slabs.

A series of stone crosses and recumbent slabs indicate a small burial site and a possible leacht. Artefacts recovered by Henry offer further insights into the community that lived at or visited Temple na Skellig. A porphyry tile fragment is probably a memento of a twelfth-century pilgrimage to Rome—the apotropaic power of objects from the holy city is specifically mentioned in a life of St Kevin, who himself travelled to Rome to bring back blessed soil to consecrate the graveyard. A beautiful cross-inscribed pin, probably used to fasten vestments in the twelfth century, is evidence for the direct presence of a high-profile ecclesiastic. Everyday earthly pursuits can be seen through the discovery of a Merels gaming board and a range of medieval ceramic vessels from Dublin, other parts of Leinster and Bristol.

Unpublished excavations

The excavations remained unpublished at the time of Henry’s death and key questions remain to be answered about Temple na Skellig, including its chronology. The bulk of the artefacts at this site date from the twelfth century; is there any evidence for an earlier date for this foundation? The excavations will form a key part of our understanding of the valley and the progression of different forms of pilgrimage. The School of Archaeology, with the assistance of the National Monuments Service, have prepared a plan for final publication of this excavation and are seeking funding to implement it.

The shores of the Upper Lake

The carefully manicured green lawns of the Upper Lake are one of the more heavily visited parts of the Glendalough landscape.

The Upper Lake plays a key role in the life of St Kevin; it is claimed that he would ‘go onto

the broad pool without boat or ferry to say mass on his Skerry’. Key archaeological features include an eleventh-century church at Reefert, a heavily reconstructed stone and earth enclosure known as ‘the Caher’, and a series of simple stone crosses set into cairns which may have marked points along the pilgrimage route. Between 2009 and 2012 we conducted geophysical survey and small-scale excavation of key features of this area.

Excavation of one of the cairn bases

Excavation of one of the cairn bases had surprising results; we found a bullaun stone securely sealed within the cairn, but a fragmentary pint glass and cigarette butts were also found beneath the cairn material, clearly indicating that the crosses have been reconstructed in recent times. A path built from flagstones was found in a number of trenches and appears to have been aligned on the cross cairn and Reefert church (Fig. 3). The flagged pathway is difficult to date but has close parallels with similar examples at

Iniscealtra, Co. Clare, and is likely to be medieval in date. The only medieval artefacts recovered at the Upper Lake were a few small fragments of Dublin-Type pottery, including some in close association with the paths. If the paths are medieval it may imply that, although reconstructed, the cross cairns at Glendalough have not moved very far from their original locations. At both monastic sites these pathways formed part of the infrastructure of pilgrimage.

The Caher

Excavations at the circular stone enclosure known as ‘the Caher’ provided intriguing evidence of the earlier settlement. The current form of the 20m-diameter monument is heavily reconstructed, but two excavated cuttings revealed that the original schist, granite and quartz stone walls of the Caher were themselves preceded by a ditched enclosure. The enclosure ditch was steeply sloping on its northern side and more gently defined to the west, measuring c. 2.2m in width and 1.4m in depth, with a narrow ‘ankle-breaker’ slot at the base. The earlier deposits within this ditch contained large smithing hearth cakes and animal bone. Hazel charcoal from these deposits was dated to AD 428–593, indicating that the enclosure was in use during the sixth century (Fig. 4). Dates for the upper levels of the ditch show that it had filled up by the ninth century and that the ditch had been replaced by a stone enclosure.

The full character of this early monument remains unclear and further dates will be obtained from the sequence of fills to help refine its chronology. While it is likely to have originally been a small ringfort enclosure, it is possible that at an early stage it was incorporated into the mythologising of the life of St Kevin. This was certainly the case in the post-medieval period, when it was part of the pilgrimage route; one eighteenth-century map calls it a ‘penitential circle’, and a nineteenth-century author says that it is one of two ‘apparently sepulchral enclosures’.

The excavations at the Upper Lake have therefore established that there was an enclosure at the time at which annalistic sources indicate that the monastery was founded. If the early origins for settlement at the Upper Lake could confirm aspects of the narrative of the life of St Kevin, what can we say about the date range and character of the main monastic site at the Lower Lake?

The Main Monastic Complex

The dating and character of the main complex would, as at many Irish early medieval ecclesiastical sites, be defined by their enclosing boundaries. The necessity of physically marking the spiritual boundaries of man ecclesiastical site is remarked on in the Collectio canonum Hibernensis. The marking of these boundaries at Glendalough is noted in the life of St Berach, who is described as walking around the civitas (ecclesiastical site) ringing his bell to cast out demons. At Glendalough the meeting of two fast-flowing mountain streams, the Glenealo and Glendassan, forms effective boundaries on the southern, northern and eastern sides, but the nature of any enclosure on the west was unclear.

Geophysical Survey

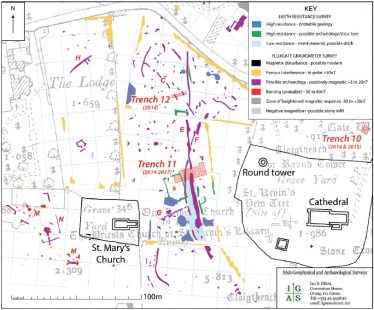

The largest seemingly empty space at the main monastic site is the field between the round tower and cemetery and the church of St Mary, a female foundation dating from the early twelfth century. A comprehensive geophysical survey of the field was undertaken by Ian Elliott in 2011 and was extended in 2015 by the Discovery Programme. These surveys revealed a large number of interesting features. The most substantial of these was a large linear anomaly, which expanded into an 8m-wide feature. Clearly the most immediate interpretation was that this was possibly an enclosing ditch or vallum (Fig. 5).

A large trench targeting this feature and an area on either side was excavated between

2014 and 2017, and the work will continue in 2018. The earliest features encountered were a series of large, stone-lined post-holes and pits. Initial radiocarbon dates indicate a mid-

seventh- to ninth-century date for this activity. A closely spaced series of pits were found, one of which contained deposits radiocarbon- dated to the mid-eleventh–twelfth century. This time-span is also suggested by a group of artefacts with a distinct emphasis on material

culture shared with the Hiberno-Norse. These include a fine gilt chip-carved mount from a

high-status, ninth-century horse harness, a late tenth-century crux issue coin of Sitric and blue glass beads. Another important find is a twelfth-century jet cross with tin inlay, probably imported from Whitby (Fig. 6). This is only the fifth example of these crosses found

in Ireland, with other examples known from Norway, northern England and Greenland.

The Ditch

The ditch itself is a very large feature, some 8m wide, containing a series of channels defined by granite and schist walls topped with very large schist slabs (Fig. 7). The areas

between the walls were filled with large granite boulders capped with smaller stones. One of

these walls contained a bullaun stone, incorporated from earlier activity. Basal deposits in the channels are water-lain. The ditch was backfilled with charcoal-rich soils containing medieval pottery—largely Dublin-Type and Leinster Cooking Ware, but also imported ceramics such as Minety-type ware and Ham Green from south-west England. The presence of medieval pottery sherds within the lowest backfilled deposits indicates that the ditch is unlikely to significantly pre-date the twelfth century. When excavations began, the ditch was interpreted as a monastic enclosure or vallum like the excavated examples at Clonmacnoise or Clonfad. The excavations have revealed something very different, and we are exploring new interpretations, such as the channelling of water between the rivers, perhaps to power a mill in the twelfth century. There is also a possibility that an earlier enclosure was remodelled to fulfil this function. A full interpretation awaits the completion of our investigations.

A Centre of Power

While Glendalough lost its importance as a diocesan centre in the early thirteenth century, it remained an important power centre of the Gaelic Irish into the later medieval period. Later medieval activity is also shown by our excavations. A plough-damaged kiln was placed on the eastern edge of the ditch feature, and charred cereals were dated to the later fifteenth century, a time when Dublin merchants were specifically sanctioning against grain sales to

Glendalough. Transitional Ware ceramics and imported Portuguese Merida Ware, often used

for pilgrim flasks, indicate this continued occupation.

Review

Our comparatively small-scale excavations at Glendalough are making an important contribution to our understanding of the complex. Many research questions remain

about the physical character of the ecclesiastical complex, and significant excavation and post-excavation challenges need to be completed to bring the project to its full conclusion. Even an interim survey of our work at Glendalough shows that considerable results can be achieved through a co-operative model involving academic bodies, multiple state agencies and the local community (Fig. 8). These can enhance interpretation, improve visitor experiences and promote this beautiful valley as a burial place, heritage site and living community.

Acknowledgements

All the work at Glendalough would not be possible without the resources and support of the National Parks and Wildlife Service, the National Monuments Service, the Office of Public Works, Wicklow County Council, the Heritage Council and the Discovery Programme. The local community, in particular through the Glendalough Heritage Forum, have been extremely supportive. Thanks to all of the volunteers, staff and students who have contributed their labour and skills to the project. Special thanks to Deirdre Burns (Heritage

Officer, WCC), Ger Dowling (Discovery Programme), Ian Elliott and Ann Fitzpatrick (NPWS). We are grateful to Mr Kevin Doyle and Chevron Yourcause for charitable support. All of the annual reports from the excavations at the field school are available at here.

Further reading

Doherty, C., Doran, L. and Kelly, M. 2011 Glendalough, City of God. Four Courts Press, Dublin.

Manning, C. 2016 Glendalough and its Churches. Archaeology Ireland Heritage Guide No. 72.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page