Glendalough and its Churches (Archaeology Ireland Heritage Guide No. 72 - March 2016)

Introduction

Glendalough, Co. Wicklow, has a remarkable collection of ruined medieval churches spread out over 3km along the valley. As a relatively unaltered group of up to nine Romanesque or earlier churches, it is unique in Ireland and Britain.

Early Irish Churches

Churches in Ireland were generally built of perishable materials such as timber, post-and-wattle or clay until about the tenth century, when stone churches, such as the cathedral

at Clonmacnoise (909), were built. All churches built in Ireland before about 1100 were simple rectangular buildings without separate chancels. Tenth- and early eleventh-century

examples have antae, pilaster-like extensions of the side walls beyond the gable walls, which supported the ends of the roof carried over the gables. By about 1050 churches were being built without antae but with corbels at the corners serving the same purpose – supporting the bargeboards at the ends of the roof. Nave-and-chancel churches and churches roofed with mortared stone first appear about 1 1 00, and some of the best and earliest examples are found at Glendalough.

History

St Kevin, who died about 620, founded the religious settlement here, which soon grew to become an important centre of learning. It was a multi-functional ecclesiastical establishment, which was partly monastic and partly concerned with pastoral care and jurisdiction over extensive lands and other churches, as well as containing a sizeable lay population.

By around 1100 one of the royal dynasties of north Leinster, the Ui Muiredaig, gained control of Glendalough with the help of the most powerful king in Ireland at the time, Muirchertach Ua Briain from Munster. The latter was also a church reformer and convened the Synod of Ráith Bressail in 1111, which laid down the boundaries of new territorial dioceses. At this synod Glendalough was made the centre of a large diocese, which in theory included Dublin. At a subsequent synod at Kells in 1152, Dublin became an archdiocese with jurisdiction over a smaller diocese of Glendalough. One of the Ui Muiredaig who had a close association with Glendalough was St Laurence O’Toole. He became abbot of Glendalough at an early age

and in 1162 was made archbishop of Dublin. After the union of the dioceses of Dublin and Glendalough in 121 5, Glendalough declined as a place of influence and importance. By the seventeenth century most of the churches were in ruins, but the site continued as a place of burial and as an important place of pilgrimage.

The Gatehouse

The main centre of the ecclesiastical settlement is located in and around the graveyard, which is still entered through the two great semicircular arches of the pre-Norman masonry gatehouse, which is unique among Irish ecclesiastical sites. This building has antae, a feature otherwise found only in churches

The Cathedral

This is a nave-and-chancel church with a sacristy attached to the chancel on the south side. The earliest part of the building is the nave, which was originally a simple rectangular church with a west doorway and window openings in the south wall. It has a feature found in the earliest masonry churches in Ireland, which date from the tenth and early eleventh centuries: antae, pilaster- like projections of the long side walls beyond the end walls. In or around 1200 a chancel arch was formed in the east wall and the chancel and sacristy were added. This work is in late Romanesque style and some of the carved stones are of Dundry Stone from near Bristol. In the fifteenth century a parapet was added, slight traces of which can be seen in the south wall of the chancel.

The Reused Stonework in the Cathedral

The lower courses of the nave walls are built of large cut blocks of local mica schist and are in stark contrast to the ordinary rubble masonry of the upper parts of the walls. These large blocks are the facing stones of an earlier smaller church with thinner walls, which was demolished to build this larger church. The earlier church had antae formed of finely cut blocks and these were reused in the present nave but were widened out at the top to the thickness of the new wall (antae are normally the same width as the walls). The west doorway was also reused from the earlier church but crudely heightened by the insertion of a stone at each side.

This doorway originally had narrow projecting jambs internally, with two pairs of slots for beams that could be slid in from the side to secure the door from the inside. These projections are now buried in the wider wall. Four D-shaped stones were also reused as ordinary building stones. These were tympana, used to fill relieving arches over doors and

windows. Rubble masonry was used in their stead over the rebuilt doorway. Examples of such stones used over windows can be seen at Confey Church, Co. Kildare. The earlier church with its deep antae could be as early as the tenth century, though the tympana, seen also over the doorway of St Kevin’s Church, would be unique in Ireland at that at that time, though not in Britian or on the Continent. The present nave was possibly built around 1100.

The Round Tower

Standing some 43m west-north-west of the Cathedral is a fine example of a round tower, a uniquely Irish type of free-standing belfry. Its round-headed doorway is over 3m above ground level and the overall height of the tower is 30.5m. It probably dates from the eleventh century.

St Kevin’s Cross and the Priest’s House

A plain granite cross with an unpierced ring stands to the south of the Cathedral, while to the west of the cross is the Priests’ House, a small enigmatic building with twelfth-century Romanesque stonework. It may have been a shrine chapel housing St Kevin’s relics but it has been much rebuilt in modern times.

St Kevin’s Church

This immediately recognisable and extraordinary small church was probably built around or shortly before 1100. Originally a plain rectangle in plan, it had a stone roof with a tiny round-tower-like belfry rising from it. Between the arched ceiling and the roof there is a narrow attic or croft. In a second phase of building, apparently not long after the first, a chancel arch was literally carved out of the east wall, cutting across the lower part of a blocked-up original east window, and a small stone-roofed chancel and an adjoining interconnecting similar structure to its north were added. The chancel was demolished about 1800 but the adjoining structure, sometimes called a sacristy, survives. Tomás Ó Carragáin has developed a theory that this church and similar ones at Killaloe and Kells were inhabited by anchorites, living in the upper part of the building, and that the so-called sacristy may be a second

anchorhold. Only the lower parts of the walls of St Kieran’s Church, a small nave-and-chancel structure a few paces to the south-east, survive.

St Mary’s Church

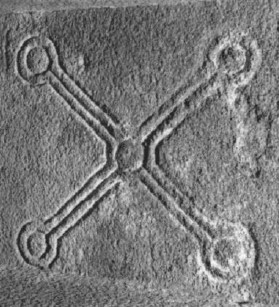

Across the field to the west of the graveyard, but approached from the road, is another nave-and-chancel church, which, judging from its name and its location just outside the main enclosure (located in recent excavations by the UCD field school), may have been a nunnery church. The earliest part is the nave, originally a plain rectangular church without antae. It has a fine west doorway with a beautiful saltire (X-shaped) cross carved on the lower face of the massive lintel that forms its head. A chancel was added possibly around 1 200 and a doorway was opened in the north wall of the nave.

Trinity Church

To the north-east of the Visitor Centre and car park and approached from the road is this remarkable nave-and-chancel church. In this case the nave and chancel were built at the same time, probably around 1100. The fine chancel arch built of large granite voussoirs remains intact. The west doorway was originally the entrance, but in a second phase of building, not long after the first, a belfry with a square base rising into a circular tower, which fell about 1820, was built against the west door. As a result, a new entrance doorway had to be opened in the south nave wall. Notable features of this building are the external corbels at the corners, which served to support the bargeboards of the roof, which was carried over the gables. Such corbels, found in Irish-style churches of the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, served the same purpose as antae in earlier stone churches.

St Saviour’s Priory

On the south side of the valley, almost 1 km downstream from the Visitor Centre, is the very interesting ruin of a small Augustinian priory of the mid-twelfth century, probably founded by St Laurence O’Toole around the time he was made archbishop of Dublin in 1162. There is some very fine Romanesque decorative carving on the east window and on the chancel arch, which was rebuilt by the OPW in the late nineteenth century. The building attached to the north side of the nave was probably where the canons lived.

Reefert Church

About 1 .5km west of the main complex, close to where a stream enters the Upper Lake from the south is another group of monuments, including a stone enclosure, small cairns with crosses and the remains of an unnamed church on the flat valley bottom. Across the stream on the rising ground to the south are Reefert Church and the remains of a circular stone cell. Reefert Church is like Trinity Church in that its nave and chancel were built at the

same time around 1100. It has a fine lintelled west doorway, two windows in the south wall of the nave and a chancel arch like that at Trinity Church. There are ancient crosses and grave-markers in the surrounding graveyard.

Temple-na-Skellig

The last of the churches is situated on the south side of the Upper Lake in a location accessible only by boat. It is a small rectangular church with a twelfth-century east window and only the lower part of a west doorway. A little to the east and even more inaccessible is St Kevin’s Bed, a tiny chamber cut into the vertical cliff face 10m above the lake, which served as a place of penitential retreat.

Politics and Patronage

Important ecclesiastical settlements such as Glendalough benefited from royal patronage, such as the building of the cathedral at Clonmacnoise by the high king, Flann Sinna, in 909. We have no historical dates for the building of any of the churches at Glendalough, but it has been argued that the building of churches here around 1100 and the promotion of Glendalough in opposition to Dublin as a diocesan centre can be attributed to High King Muirchertach Ua Briain, ally of the Ui Muiredaigh. He may have been trying to emulate or even surpass the multiplicity of churches that were in Dublin by this time and make Glendalough fit to be the superior see.

Ironically it was Dublin that won out, firstly at the Synod of Kells in 1151, when it became an archbishopric, and secondly in 1215, when Glendalough was subsumed into the Dublin

diocese. The addition of the chancel to the Cathedral, with its use of foreign building stone as at Dublin’s Christ Church, appears to be an attempt to modernise the building in order to

justify its continued existence as a diocese before the long-threatened union happened.

Further Reading

Doherty, C., Doran, L. and Kelly, M. (eds) 2011 Glendalough : City of God. Dublin.

Leask, H.G. (n.d.) Glendalough , Co. Wicklow. Dublin.

Manning, C. 2002 A puzzle in stone: the cathedral at Glendalough. Archaeology Ireland 16 (2), 18-21 .

Manning, C. 2007 A suggested typology for pre-Romanesque stone churches in Ireland. In N. Edwards (ed.), The Archaeology of the Celtic Churches , 265-80. Leeds.

Ó Carragáin, T. 2010 Churches in early medieval Ireland : Architecture , Ritual and Memory. New Haven and London.

Credits and acknowledgements – Guide series editors – Tom Condit and Gabriel Cooney

Text- Conleth Manning

Photography – Photographic Unit, National Monuments Service.

Thanks to Tony Roche for supplying the images.

Text editor – Emer Condit

Typesetting – Wordwell Ltd

Circulation manager – Una MacConville

Date of publication: March 201 6.

To order this guide please contact: Archaeology Ireland ,

Unit 9, 78 Furze Road, Sandyford Industrial Estate, Dublin 18.

Tel. 01 2933568

Design and layout copyright Archaeology Ireland. ‘

Text copyright the author 201 6.

ISSN 0790-982X

This guide has been generously supported by the Office of Public Works.

Comments about this page

Thank you for this very interesting article with delightful images plus sketches of this famous retreat. It is a holistic experience to visit.

Add a comment about this page